Vitruvius, pt. 2: Read This If You Like Being a Sm•rtass

The "Ten Books" on architecture is necessary reading if you really want to annoy everyone around you with your 'useless' knowledge of Greek & Roman temples.

Ancient Greek and Roman temples are famous the world around for their imposing figure and delicate ornamentation. As I discussed in my previous post on Vitruvius, there are five “orders” (closely regimented styles): Doric, Ionic, Tuscan, Corinthian, & Composite. These are primarily defined and identified by their columns, though each order governs the entire temple’s construction. I will outline these in as much detail as concisely as I can. If you really want to annoy the hell out of everyone around you, this is the article for you. Buckle up.

Share this post with your favorite sm*rtass!

The Doric order derives its proportions from the typical male’s proportions (7:1). This makes it the “masculine” order. The Ionic order derives its proportions from the typical female’s proportions (9:1), making it the “feminine” order. The Corinthian and Tuscan orders are different. The Tuscan order is very simple, dating back to the foundation of Rome, long before their prodigious wealth. The Corinthian order, on the other hand, postdated Corinth’s wealth,1 and was developed as a sumptuous style that would better fit Corinth’s wealth than the delicate Ionic style. The Composite order is a combination of the Ionic and Corinthian order. One does not mix orders, except in the composite order. (Palladio, as we will see in a future piece, lays out principals for mixing orders, but he is nearly 1,000 years after Vitruvius.)

Before we may discuss the specifics of each order, we must first establish the vocabulary of temples in general. The capital of the column is where the column meets the architrave. It is roughly cubic or conic in its shape, though the column is cylindrical. It is the most ornate portion of the column in each order. The plinth is the bottom portion of the column. The shaft is the middle portion. The flutes are the smooth grooves running along the shaft of the column to the capital. They can be vertical or spiral up the column at an angle. A column shaft can also be smooth. Fluted columns should have 20 flutes.

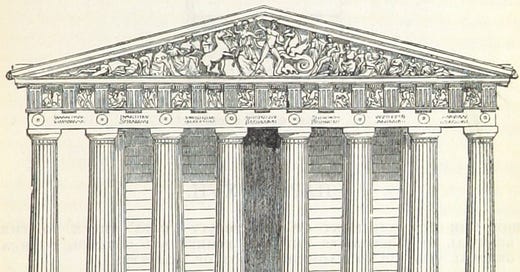

The architrave is the stone portion of the building supported by the columns. The frieze is the portion above the architrave that features relief images. Sinae are the upturned edges of a temple roof that act as gutters. These—according to Vitruvius—should feature lions’ heads. Those lions centered on columns should have holes in their mouth so that they spit water when it rains and people may take shelter in the colonnade without getting drenched by the lions. Antae are walls that do not completely enclose an interior space in the temple; they should be as wide as a column. The timpanum is the semi-circular or triangular carving above a door. The pediment is the large triangular frieze above the outermost frieze.

Taller columns require a certain adjustment to the diameter of the shaft. This is known as entasis. The shaft at the base will be a certain width and will narrow as it approaches the capital, so that it is much more narrow than at the top of the shaft. I have tried to make it clear in the labelled image of the Parthenon by placing a vertical line next to a column to show the curvature of the shaft.

And just for fun: acroterion are the ornamental statues placed on the roof of the temple. An acroterion angularium is when an acroterion is placed at all four corners of a building’s roof. Pilasters are the flattened ‘columns’ laid in the face of the building; these also conform to the five order’s rules. Telamones or atlanes are columns carved in the shape of humans. These are comparatively rare in classical temples and were not common enough to have their own rules

Each order has something that distinguishes its columns. For the Doric, it is its lack of a plinth and simple capital. For the Ionic, it is the “cushion” shaped capitals. For the Corinthian, it is the acanthus leaves (symbols of immortality in Greece). For the Tuscan, it is a plinth and abacus (a sort of inverted plinth that replaces the capital; it is a smooth cylinder). Finally, the Composite order combines the cushion and acanthus in the capital.

Beyond the columns, there are other prominent ornaments that are only permitted in one style or another. Dentils (meaning “teeth”) are only allowed in the delicate Ionic, Corinthian, or Composite styles. I pulled an image from my piece on the Old Parkland’s Debate Chamber which featured dentils. Triptychs and metopes are unique to Doric temples. These are the parts that compose the frieze. The triptych is a stone with three vertical grooves that covers the ends of wooden rafters. The metopes are individual relief images carved in stone and set between the triptychs.

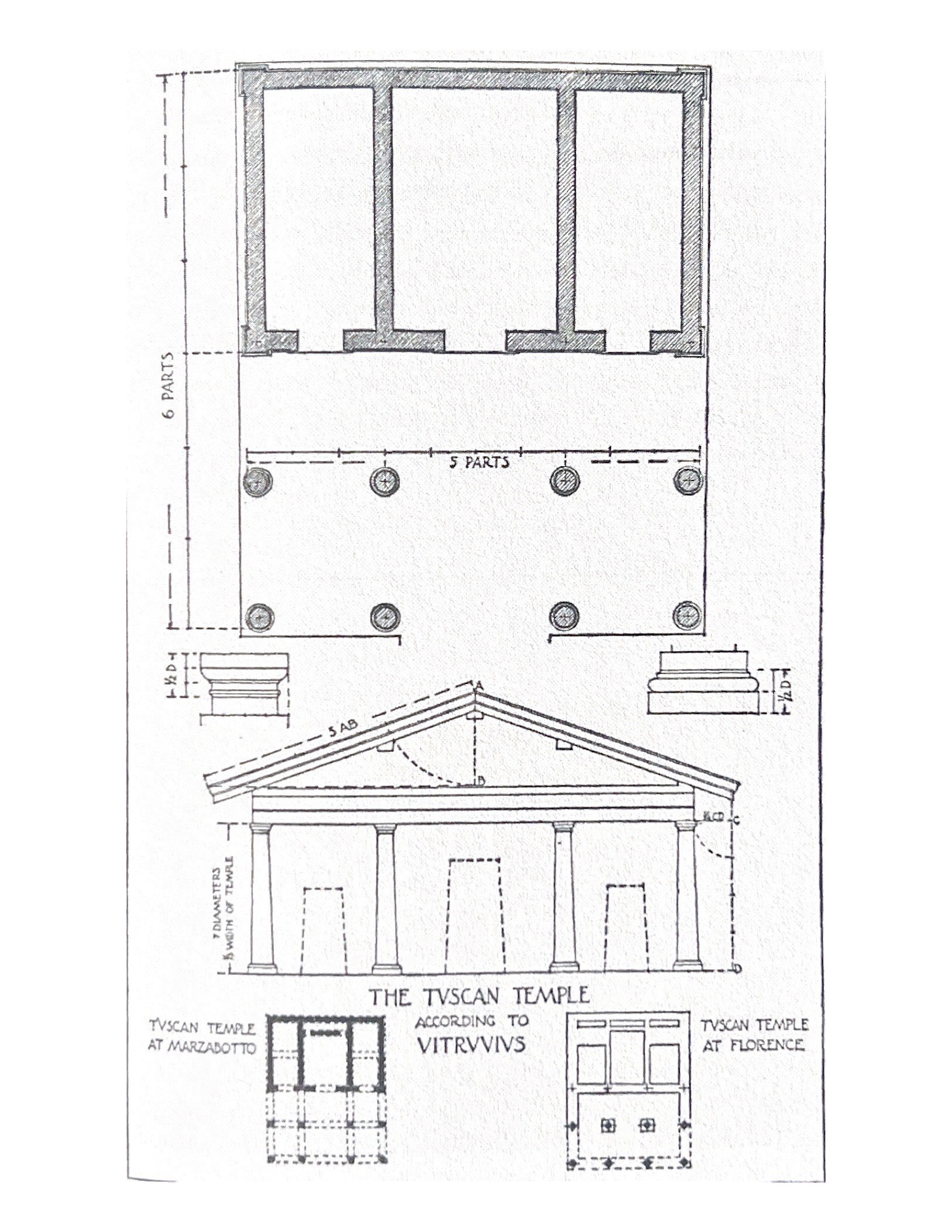

Tuscan temples are built on a different plan than Greek temples owing to their separate development in a distinct culture. The width should be 5/6 the length. They feature one or three cells, one for each god. Half of the area of the temple is taken up by the pronaos, which is the Tuscan colonnade and porch. The roof has a shallower pitch than in Greek temples, and the columns are spaced much farther apart.

Each column may be built to just about any height. Vitruvius therefore provides us with the proportions that govern each column. Each is determined by the “unit” of the column, typically the width of the column at the base. The width of the column serves as the unit for most of the temple. The spacing of columns, the width of walls, and the size of metopes & triptychs is determined by the width of the column.

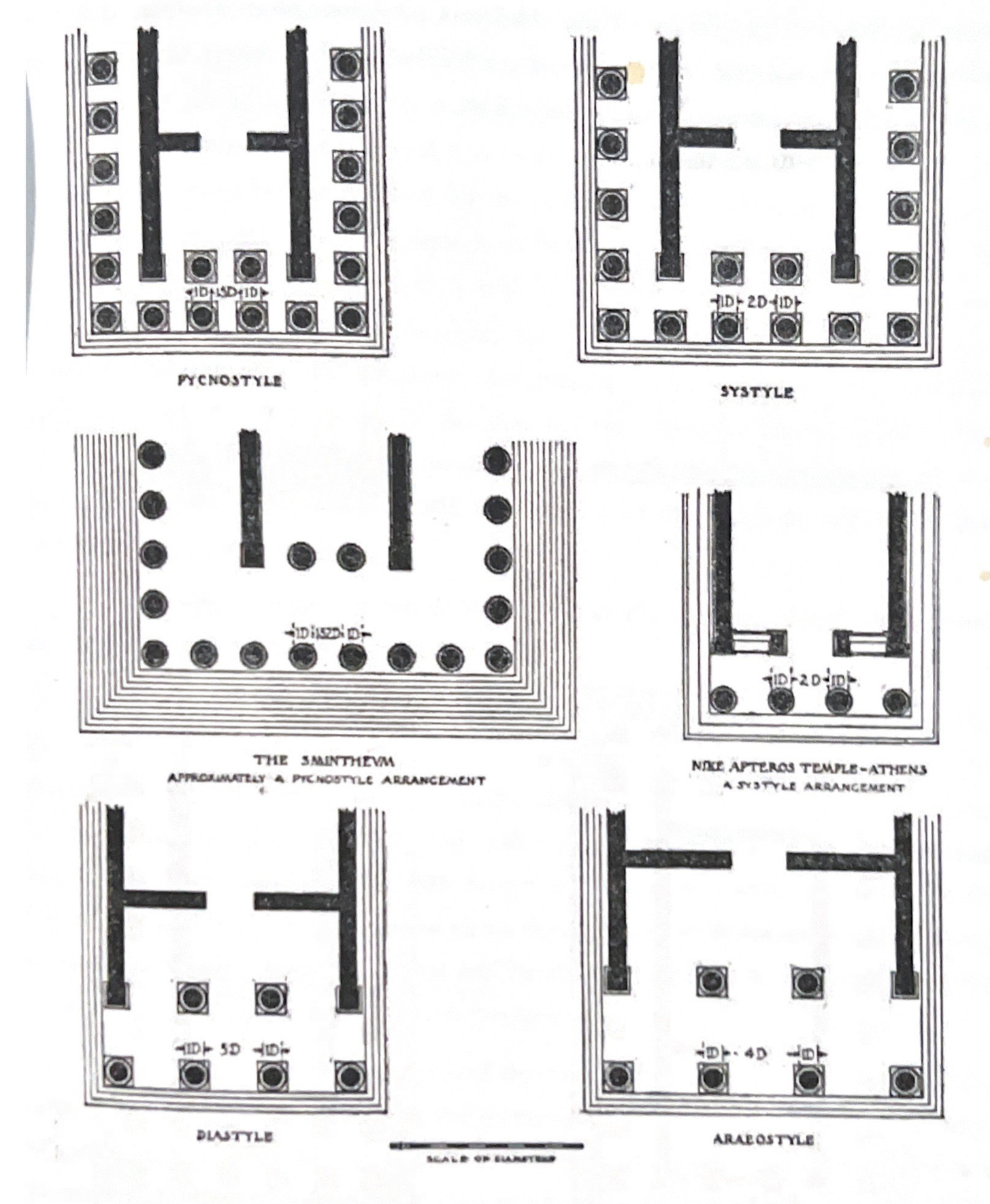

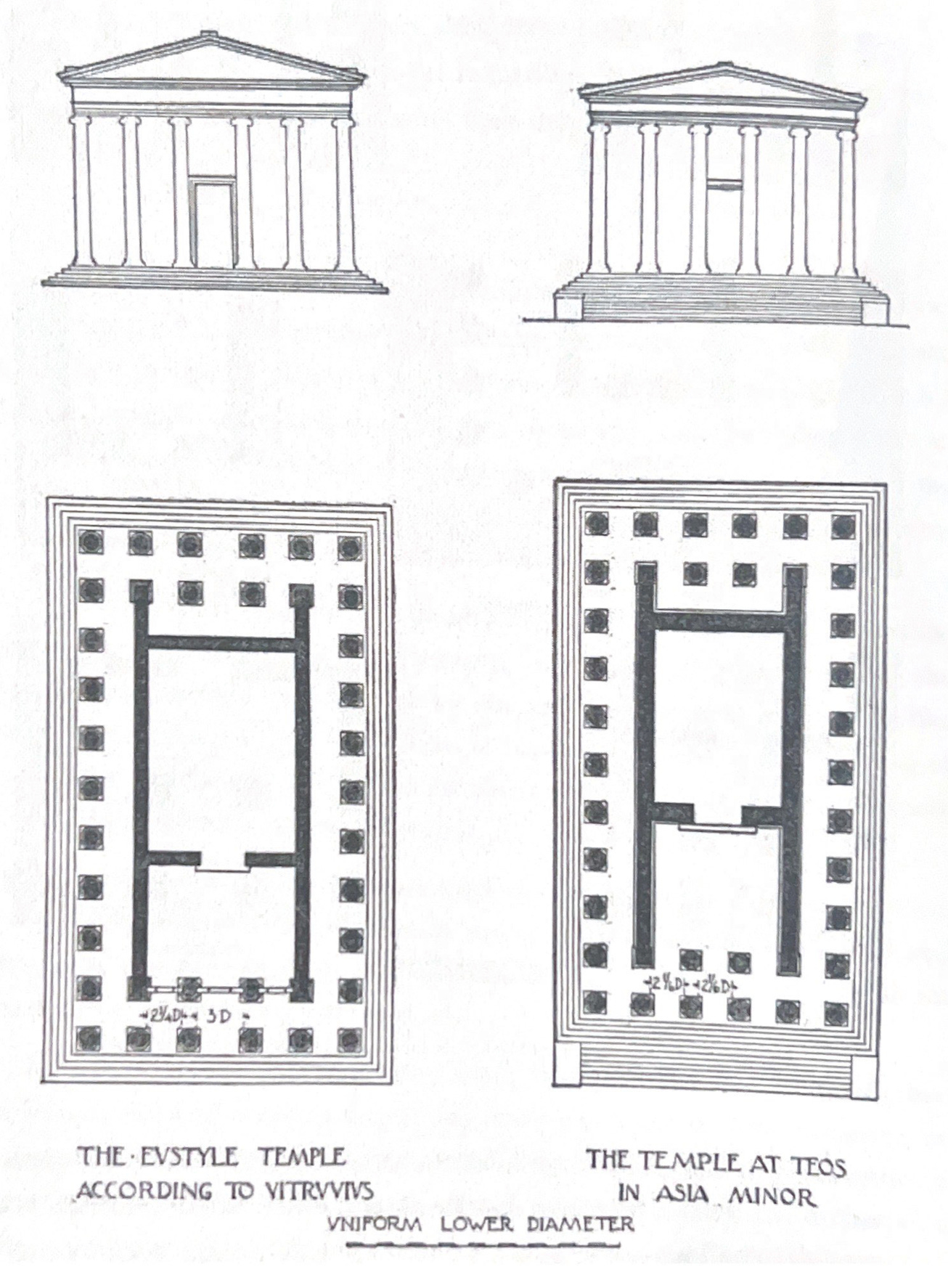

More generally, Greek temples are twice as long as they are wide, though their colonnades have 2n-1 columns in the lengthwise colonnade than the shorter colonnade. Further, there are many different arrangements of Greek temples. I will not go into what defines each style, but the variables in all are: spacing of columns, number of colonnades, layout of walls, and layout of colonnades. All styles adjust the width of the space between the columns that flank the door to allow processions to pass through them more easily. Vitruvius says the eustyle is the best because of its proper spacing of columns which allows one to fully see the doorway while standing beyond the colonnade.

Circular temples were only constructed by the Romans. They come in two styles: monopteral (without a cell, that is, exposed to the open air) or peripteral (with an enclosed cell and doors). In the monopteral style, the columns’ height and dome’s diameter are equal in height to the diameter of the temple. In the peripteral, they are both 1/2 the temple’s diameter. The finial is the ornament atop a dome. It should have the same proportions as the capitals of columns.

Thus are ancient pagan temples according to Vitruvius. Go forth and drive your friends and family crazy.

According to Vitruvius, when Athens lost the Peloponnesian War, the lucrative Black Sea grain trade which gave it its wealth transferred to Corinth. In addition, Corinth sat on the highly strategic isthmus of Corinth, which was the preferable route around the Peloponnese (for oceanographic reasons that I do not quite understand: suffice to say, the other route was too rough for much of the year).