Schizopolis: All the World's a Madhouse

Iain McGilchrist's magnum opus - "the Master & His Emissary" - lays out how the neuropsychological reasons our architecture is driving us all crazy.

“I feel that we have lost not just the plot, but our sense of the absurd. we stand or sit there solemnly contemplating the genius of the artwork, like the passive, well-behaved bourgeois that we are, when we should be calling someone’s bluff. My bet is that our age will be viewed in retrospect with amusement, as an age remarkable not only for its cynicism, but for its gullibility.”

- Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 442

The Master and His Emissary (2009) is a dense and wide ranging book which attempts to explain both the inner functionings of the human mind by means of the differences in the hemispheres of the brain and how our society has become so wealthy and populous yet meaningless and atomized. The last part of the work deals directly with art, and McGilchrist’s theory that our modern, Western culture and environment encourage an unhealthy schizoid mentality. While he covers a staggering range of topics, I will only really touch on his theory as it relates to schizophrenia.

McGilchrist takes over 100 pages to precisely develop his split-hemisphere theory, the evidence, and its implications in countless scenarios. I will try to summarize the ideas in a short space.

The Differences of the Hemispheres

The left and right hemispheres of the brain are specialized in their functions, though either one is capable of performing the functions of the other to a lesser degree. The left specializes in the particular. It sees parts, thinks abstractly, and builds up from smaller pieces. It is better at inductive reasoning, struggles to perceive whole objects, and is egotistical. The right hemisphere sees wholes, thinks concretely and in context, and works from the whole down to the parts. The right hemisphere is better at deductive reasoning, struggles to see parts of objects in detail, and sees the interrelatedness of everything. Interestingly, the right hemisphere seems to survey our surroundings, then, when something worth paying attention to pops up, it send a stimulus to the left hemisphere so that we might pay more careful attention. After the left hemisphere has analyzed the subject of its attention, the information is returned to the right hemisphere for it to be re-integrated into its surroundings and understood in-context.

He illustrates the relationship between the hemispheres using a metaphor borrowed from Nietzsche where there is a Master and his Emissary. The Master, being a ruler, needs the Emissary to carry out his orders, as he is but one man. The Emissary, in carrying out the orders, handling problems, and being obeyed, begins to think he can replace the Master and do his job better. The Emissary thus overthrows the Master and takes his place, only to discover that there he does not does not know how to answer the various questions placed at his feet. The country falls into disarray, and the Emissary cannot understand why. In McGilchrist’s estimation, the left hemisphere is the Emissary and the right hemisphere is the Master. The left hemisphere carries information back and forth, process and improving it in vital ways, but still ultimately serving the overarching vission of the right hemisphere. Crucially, the left hemisphere cannot understand the thought process of the right hemisphere, and therefore, rejects it as false. The right hemisphere, though, can understand the perspective of the left.

If you are interested in learning more about McGilchrist’s research, he discusses it in a recent interview about his new book the Matter With Things on Dr. Jordan Peterson’s podcast. Two years ago, they spoke about the Master and His Emissary.

Schizophrenia As Left-Hemisphere Domination

Throughout the work, McGilchrist continually returns to the theory that schizophrenia is an absolute and uninhibited domination of the left-hemisphere mode of thinking. In my opinion, the strongest evidence for this is that “In cases where the right hemisphere is damaged, we see a range of clinically similar problems to those found in schizophrenia.”1 He lists the parallels:

“Both appear to have a deficient sense of the reality or substantiality of experience (it’s all play-acting), as well as the uniqueness of an event, object or person. Perhaps most significantly, they have a similar lack of what might be called common sense. In both, there is a loss of the stabilizing, coherence-giving framework-building role that the right hemisphere fulfills in normal individuals. Both exhibit a reduction in pre-attentive processing and an increase in narrowly focussed attention, which is particularistic, over-intellectualising [sic.], and inappropriately deliberate in approach. Both rely of piecemeal decontextualized analysis… Both tend to schematize - for example, to scrutanise the behavior of others, rather as visitors from another culture might, to discover the ‘rules’ which explain their behavior.”2

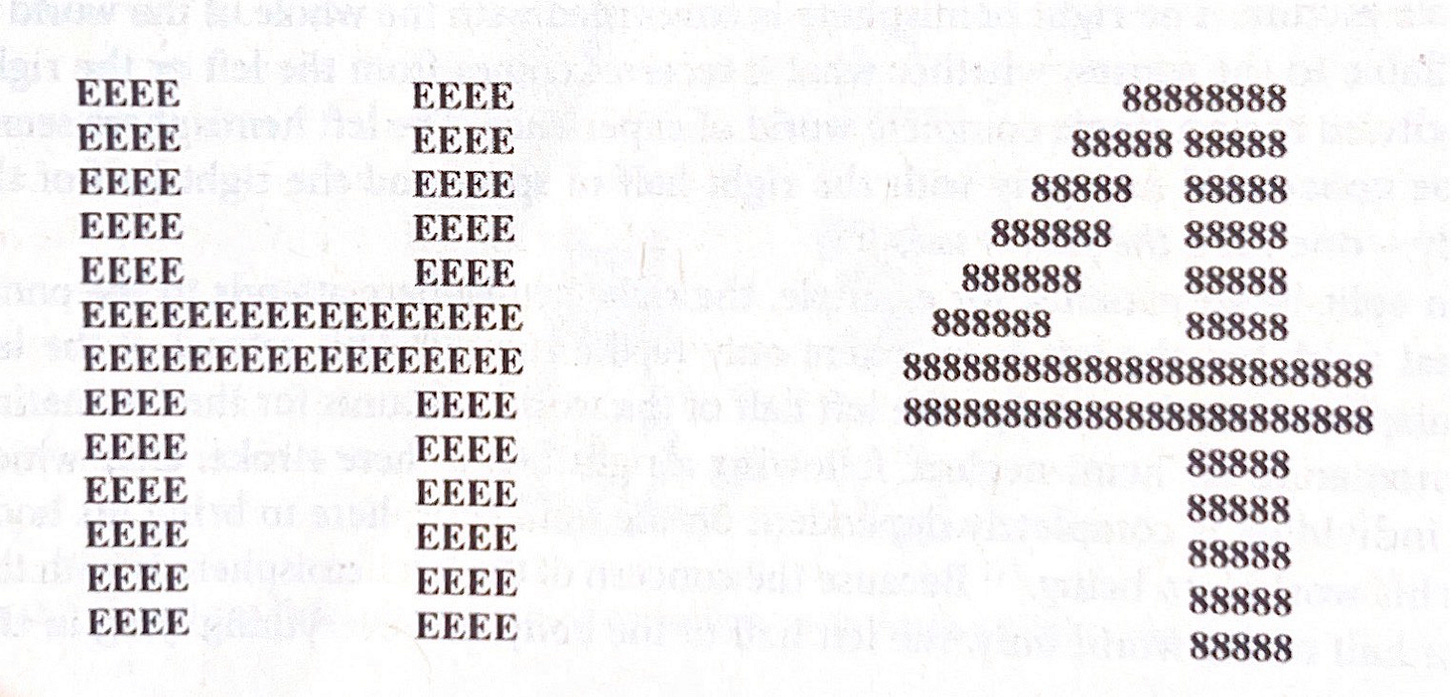

To exemplify it, he details research which has found that when those with and without schizophrenia are presented the image below and asked what the picture protrays, those with schizophrenia say they perceive a mass of Es and 8s. The right hemisphere’s ability to perceive the whole is absent, and the left hemisphere cannot adequately compensate to compose the whole from the parts.3

Interestingly, the drugs that successfully reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia disproportionately reduce activity in the left hemisphere.4

He loosely defines schizophrenia as “not characterized by a romantic disregard for rational thinking and a regression into a more primitive, unself-conscious, emotive realm of the body and the senses, but by an excessively detached, hyper-rational, reflexively self-aware, disembodied and alienated condition.”5

McGilchrist argues that schizophrenics and those with similar manners of thinking cannot move beyond the parts to the whole in any context. The implication is that the world dissolves and divides, becoming an un-living world that lacks meaning or consistency. He believes that Rene Descartes exemplified schizotypic thinking when he came to his famous declaration: cogito ergo sum.

“[Descartes] saw the body, the senses and the imagination as likely to lead, not only to error, but into the realm of madness… [Schizophrenia] entails in many cases a wholesale inability to rely on the reality of embodied existence in the ‘common-sense’ world which we share with others, and leads to a dehumanized view of others… One’s own body… is seen as just another object, sometimes a disturbingly alien object, in the world that is validated by cognition alone.”6

What’s more, philosophical thinking itself, with its detached and distanced self-analysis, leads to schizophrenic thinking. McGilchrist does not consider this methodology healthy or conducive to discovering the truth. Descartes himself doubted whether he had a body at all!7

This mode of thinking, which is detached from the physical world, which places thought above observation and doubts the reality of others, came to dominate during the Enlightenment. The human was most often analogized as a machine. That ridiculous notion has since died out. We enlightened moderns know that the body cannot be reduced to something so simple as an automata. Our brains, like computers, have developed beyond that idea.

Descartes also struggled to perceive the continuity of time, instead describing it as a series of frozen instances occurring in succession. McGilchrist concludes “that in all its major predilections…the philosophy of Descartes belongs to the world as construed by the left hemisphere.”8

Behavioral Symptoms of Schizophrenia (& Modern Art)

Schizophrenics have no sense of depth. “Depth,” as used by McGilchrist, is a metaphor. He defines it as “both the means by which we are drawn into a felt relationship with something remote (rather than just observing it, which would be the effect of a flat plane), and, at the same time and inseparably, the incontestable evidence of separation from it.”9 But depth is also meant in a literal sense. Schizophrenics lose a sense of depth and modern art and architecture are devoid of perspective.10 And perspective is our means of picturing ourselves within the art; it forces the subject into a particular time and place in relation to the object.11

“Beauty is rarely mentioned in contemporary art critiques: in a reflection of the left hemispheres values, a work is now conventionally praised as ‘strong’ or ‘challenging.’ “

- Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 443

Additionally, since the left hemisphere cannot understand the right’s perspective, schizophrenics feel that there is a vast world hidden from them. They know that there is something they do not know, but they cannot figure out how to access it. The left hemisphere can only come to know things through careful, directed, and abstract thought, which leads schizophrenics stare at things in search of the hidden meaning.

“The more one stares, the more one freights them with import. That man crossing his legs, that woman wearing that blouse - it can’t just be accidental. It has a particular meaning, is intended to convey something; but I am not let in one the secret, which every one else seems to understand.”12

This is the source of schizophrenic paranoia. Is it any wonder that the world seems “threatening, disturbing, sinister” to them when that is how they see the world?13

The same mentality is seen in modern art. Art is meaningless, so sayeth the artists. Yet, the works are utterly overflowing with meaning, so sayeth the self-same artists. Modern art, for both the artist and the observer, becomes a “ ‘form of drama in which consciousness watches itself in action’ (Valéry);”14 modernist artists “accept an explicit manifesto or message… as a substitute for imaginative experience: this is apparently a coded message, which thereby flatters the decoder.”15

And the relationship gets worse! Those modernists who throw paint at a canvas and pontificate about it as a commentary on “capitalism” or “misogynoir” or “democracy” are exactly the same as schizophrenics when given a Rorschach test! Schizophrenics will either describe the exact shape and quality of the blots or claim they represent abstract concepts like “democracy” or “motherhood.”16 Here we see that the tendency of modernists to create formless works and then declare their deep meanings is not a sign of profound thought, but instead a symptom of profound sickness. They are not well. Applauding and rewarding their illness will not improve their state.

The values of modernist artists are contrast, shock, offense, boldness, & novelty. This also mirrors the schizophrenic mind. McGilchrist points out that, as the world is drained of meaning, a sense of boredom sets in. That which was formerly full of life is now without vitality. “Bizarre, shocking, and painful ideas or actions may be welcomed as a way of trying to relieve this state of numbed isolation.”17

Environmental Schizotypy

Worryingly, modern art, and especially modern architecture, appears to induce schizophrenic thinking in otherwise normal people. Those who live in cities are nearly twice as likely to suffer from schizophrenia. Those in developed countries are more prone to schizophrenia. Immigrants that lose their cultural and communal ties are more prone to schizophrenia than those that maintain them. McGilchrist is concerned that “if a culture starts to mimic aspects of right-hemisphere deficit, those individuals who have an underlying propensity to over-reliance on the left hemisphere will be less prompted to redress it, and moreover will find it harder to do so.”18

Modernist art is not some harmless and quirky aberration that we can simply laugh off because humans do not exist independent of our environment. We are not slaves to our surroundings, but they certainly set us down one track over another. Modernist art must be opposed, since it blights our environment and demoralizes us.

Implications for architecture

McGilchrist, interestingly, thinks that architecture and music are the most resilient arts in the face of modernist and post-modernist assaults. It is asinine to ask what the “purpose” or a building is.

Further, unlike a painting, book, or movie, architecture cannot be removed from its context. And every context is necessarily unique. Modernists rankle at the thought. They desire to universalize. Mies van der Rohe “declared an outright refusal of all local colour; only the abstract and universal were to be admitted.”19

That said, he does not think modernist architecture is by any means good. He notes that “straight lines exist nowhere in the natural world, except perhaps at the horizon.” He lists the myriad causes for our misery, as created by our environment:

“I would contend that a combination of urban environments which are increasingly rectilinear grids of machine-made surfaces and shapes, in which little speaks of the natural world; a worldwide increase in the proportion of the population who live in such environments, and live in them in greater degrees of isolation; an unprecedented assault on the natural world, not just through exploitation, despoliation and pollution, but also more subtly, through excessive management of one kind or another, coupled with an increase in the virtuality of life… have largely created an insubstantial replica of ‘life’ as processed by the left hemisphere…”20

We have been severed from "the uniqueness of place, what [Anthony Giddens] calls ‘locale.’ "21 The home, according to Le Corbusier (the failed destroyer of Paris), is but a machine to inhabit.22

McGilchrist goes farther than I did. Not only architecture, but the entire artistic “tradition is an embodiment of a culture: not an idea of the past, but the past-itself embodied,”23 (Emphasis his). He even argues that research suggests a “remarkable agreement in what is perceived as consonant and pleasurable and what is seen as dissonant and disagreeable” across “different cultures and from different generations.” Moreover, the right hemisphere processes consonance, and the left hemisphere processes dissonance.24 This is a shocking blow to aesthetic relativism, and reveals why schizoid artists and the common man disagree on nearly every point of aesthetics.

This essay covered only a small fraction of McGilchrist’s work. If you are interested in his work, I highly suggested you purchase the Master & His Emissary or the Matter With Things. I have not read the latter, but I have heard from friends that it gives a good summation of the first work. The Master & His Emmisary will certainly go down in history as one of the greatest works of this century. Almost all of McGilchrist’s predictions for our society, which were not obvious in 2009 at all, are already coming true.

Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: the Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), New Expanded Ed., p. 392.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 392.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 43-44.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 393.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 332.

Ibid.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 333.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 334-5.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 362.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 398.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 300.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 399.

Ibid.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 398.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 410.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 401.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 396.

McGilchrist also notes that there does not appear to be anything that draws schizophrenics to cities at a disproportionate rate, suggesting that the cities are the cause. McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 404.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 416.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emsisary, p. 387.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 390.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 416.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 358.

McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, p. 419.